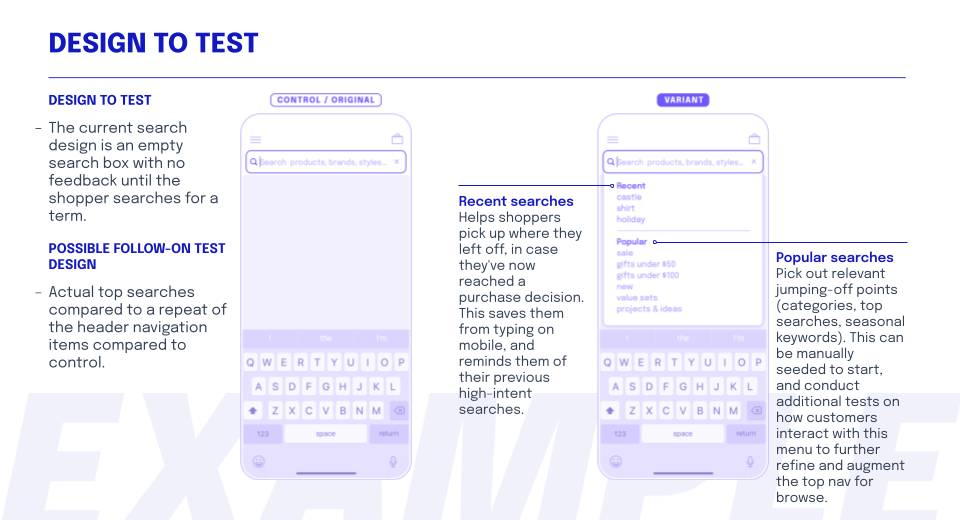

I was tasked with developing an A/B testing curriculum for a portfolio of direct-to-consumer eCommerce for a mobile version of the online customer portal.

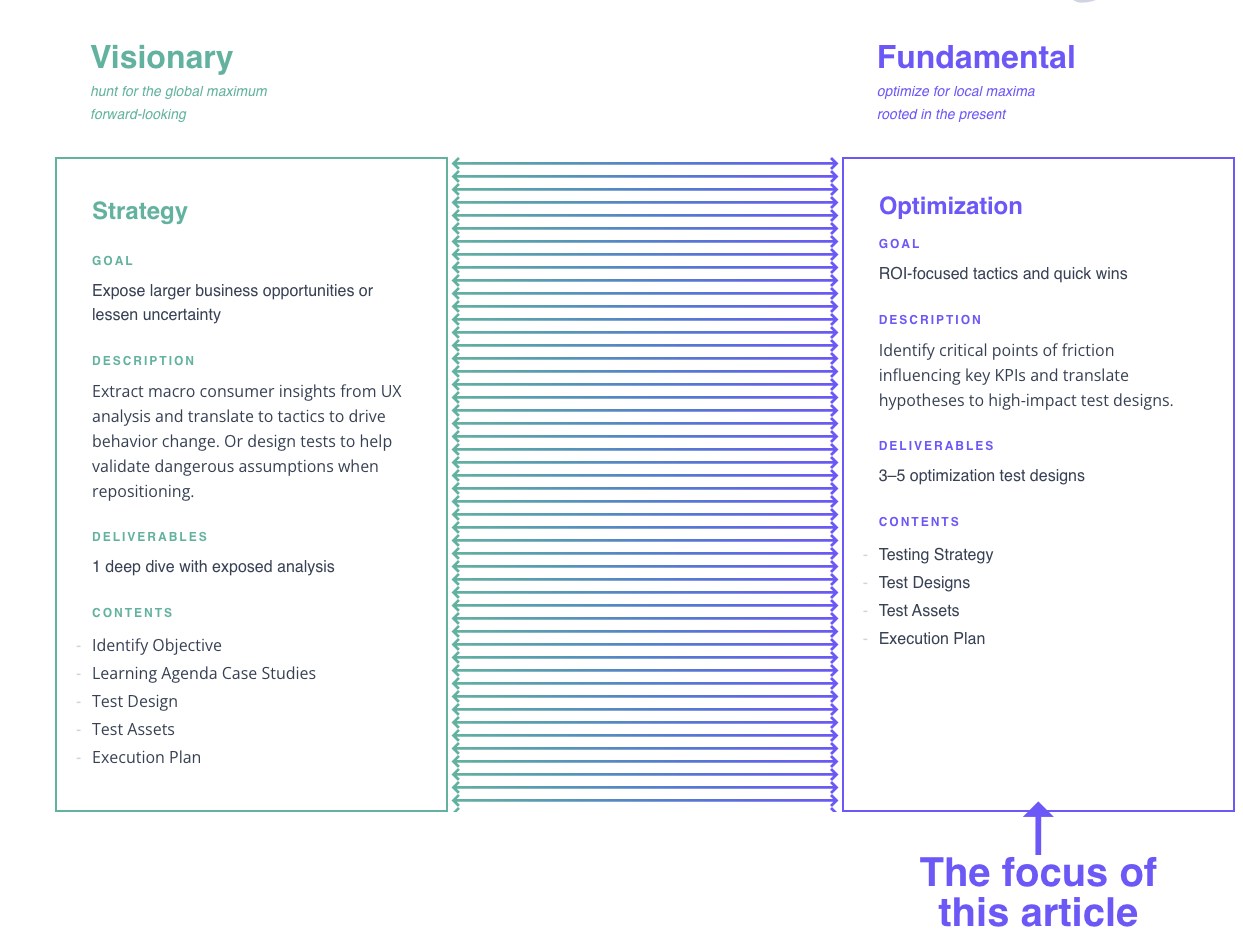

Since then, I’ve worked with analytics collaborators to develop our own framework to use with eCommerce clients in a test, learn, and iterate approach. It helps us efficiently uncover opportunities, form hypotheses, align with business leaders, and collaborate with product teams.

Although clients still present new challenges that compels us to adapt our thinking and process, here’s what we’ve learned so far:

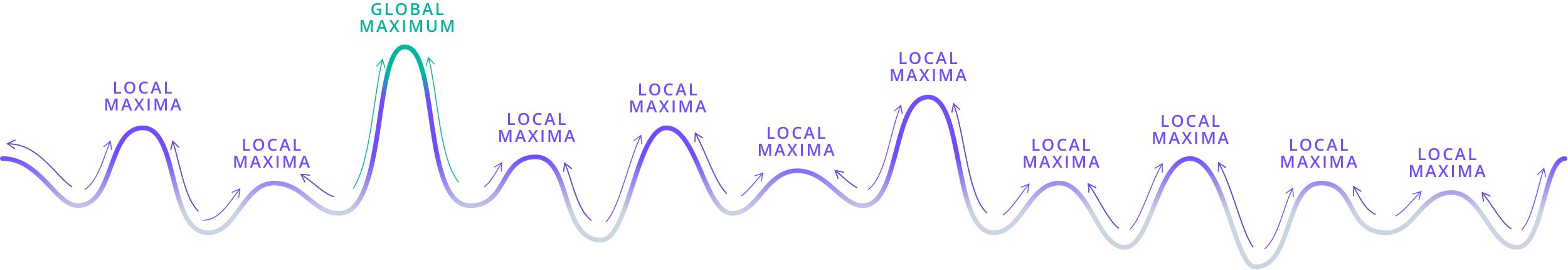

Why A/B testing is worth doing

What testing can and can’t accomplish

The three principles we follow for optimization

Our goal was to create a framework so that A/B testing becomes an engine that reliably delivers real business value in the form of increased revenue or customer insights. It also needs to be light-weight enough to address all the earlier objections: not enough time, not enough impact to justify the time investment, and results are too often inconclusive or not widely applicable to be valuable.

We distilled our approach down to three principles:

- Low effort ↓

to develop, deploy, and analyze - High impact ↓

for business goals and customer development - High confidence ↓

in the hypothesis based on available information

Let’s take a closer look at each of these.

1. Low effort

Keep things simple, both conceptually and executionally. One of the most common reasons teams fall off on testing is it ends up taking too much time. Even super enthusiastic teams are at risk of overextending — designing excellent, but complicated tests which are time-consuming to launch, and also difficult to analyze. It’s almost always better to build and keep momentum by launching several smaller tests, than to design one giant test that becomes higher-pressure to deliver positive results.

Conceptually, this means that nothing is being drastically reevaluated and post-test analysis will also be more manageable.

Executionally, our goal is to fit design and engineering into one sprint. When designing, what’s the leanest implementation to test this hypothesis?

2. High impact

There’s always going to be interesting data everywhere. From a conversion rate optimization standpoint, this is a trap we worked hard to avoid.

One trap of interesting data is wasting time in the analysis stage. Whenever you open Google Analytics, there’s always going to be an anomaly begging for investigation. It’s dangerously addictive to go down each of these “interesting data” rabbit holes and try to solve each one as a puzzle — before you know it, hours have flown by and you don’t have anything actionable.

Another trap is investing time implementing clever solutions that might have a large impact (even doubling or tripling conversions!), but on a feature that only reaches a tiny segment of visitors. Unless there’s a valuable customer learning, we’d consider this a failure from a conversion rate optimization standpoint.

To avoid analysis paralysis and to identify high-impact potential tests, we followed these three criteria:

- High traffic / engagement areas so that even a small lift would yield meaningful results.

- High revenue areas where even a small lift in traffic / engagement would yield meaningful results.

- A valuable learning, such as validating a dangerous assumption.

3. High confidence

Lastly, we optimized for hypotheses that we’re most confident in, rather than speculating on unknowns. This meant:

- Form an opinionated and focused hypothesis (to avoid testing too broadly and risking inconclusive results).

- Capitalize on existing behavior (instead of trying to change or influence new behavior, which is risky and difficult).

- Focus on what’s not working (leave personas, features, and flows that are working alone).

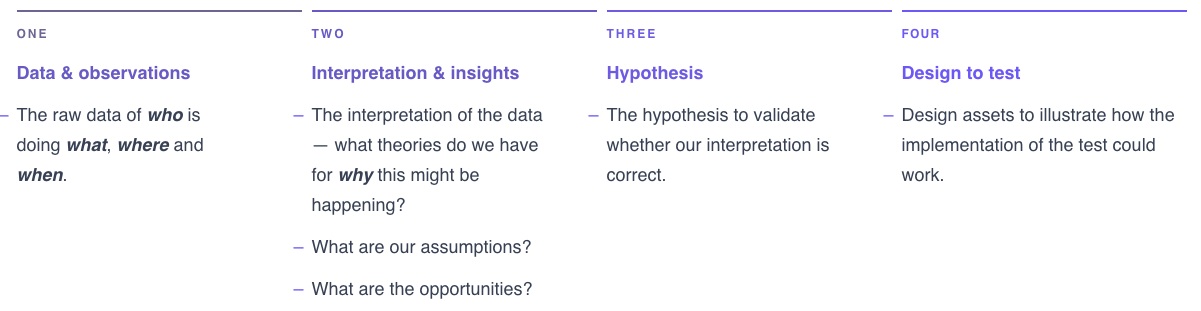

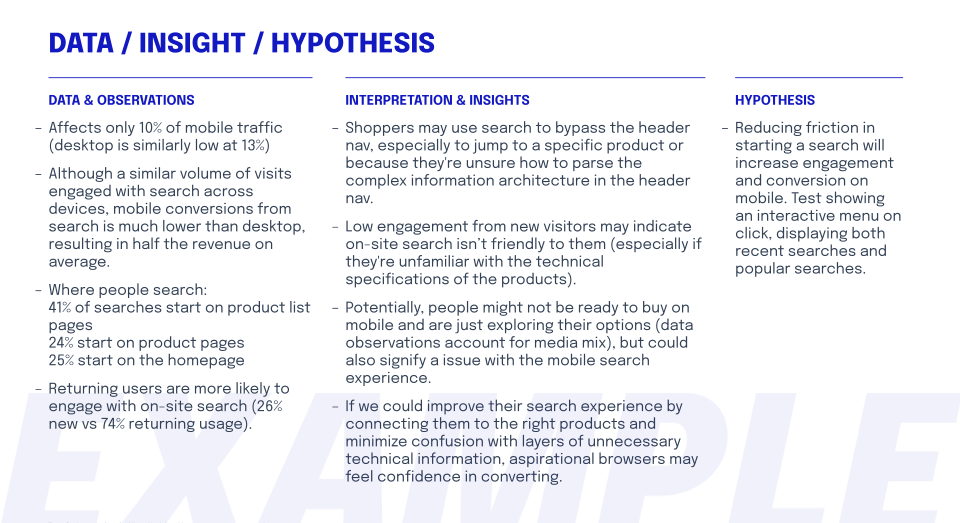

Test Design Format Opportunity discovery